California has become the first state to ban most law enforcement officers, including federal immigration agents, from covering their faces while conducting official business. Governor Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law on Saturday in Los Angeles, a move that has already ignited a fierce clash with the Trump administration.

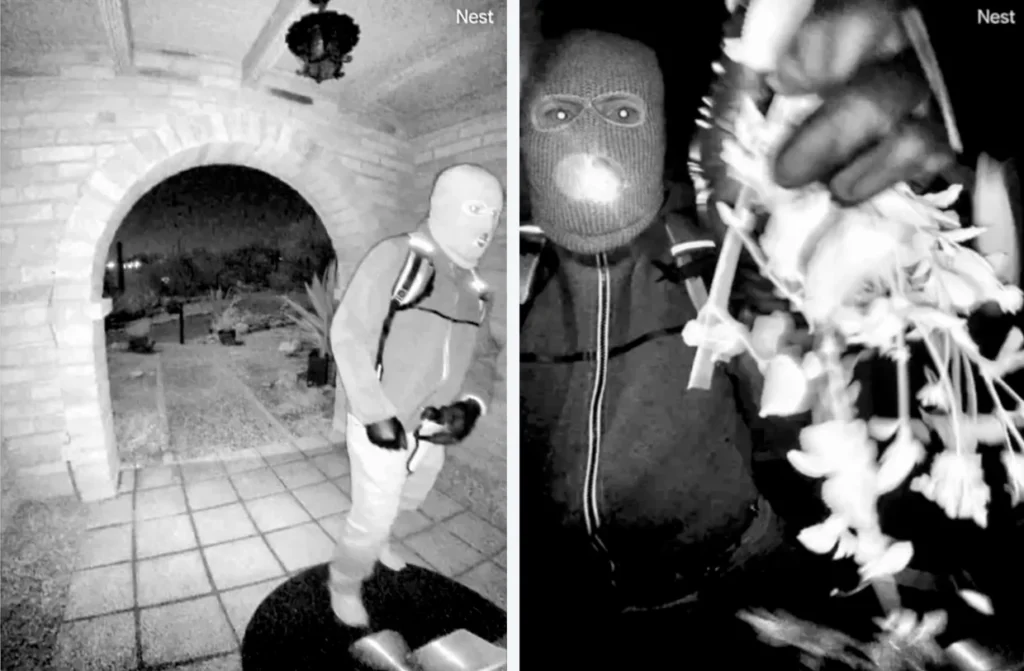

The legislation is a direct response to recent immigration raids in Los Angeles where federal agents wore masks during mass arrests, fueling public outrage and days of protest. President Donald Trump escalated tensions by deploying National Guard troops and Marines to the area, intensifying the standoff between state and federal authorities.

At a press conference in Los Angeles, Newsom stood alongside state lawmakers, educators, and immigrant community leaders, highlighting that 27% of Californians are foreign-born. He framed the new law as part of California’s broader defense of immigrant rights, saying, “We celebrate that diversity. It’s what makes California great. It’s what makes America great. It is under assault.” Newsom criticized the use of masked agents and unmarked vehicles, likening the practice to a dystopian science fiction scene where people “quite literally disappear” without due process.

The law prohibits officers from wearing neck gaiters, ski masks, and other facial coverings during official duties. Exceptions are made for undercover agents, medical masks such as N95 respirators, and tactical gear. The restrictions also do not apply to state police. Supporters argue that the measure will help restore trust in law enforcement and prevent impersonation of officers for criminal activity.

Trump administration officials, however, quickly denounced the law. Acting U.S. attorney for Southern California Bill Essayli dismissed California’s authority over federal agencies, stating the ban has “no effect” on federal operations and that agents will continue to conceal their identities for safety. He also criticized Newsom for a comment about Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, saying the matter had been referred to the Secret Service.

Homeland Security assistant secretary Tricia McLaughlin went further, calling the law “despicable” and accusing Newsom of endangering federal officers. She argued that agents face violent threats from rioters and extremists and that masks are necessary to protect them from harassment, doxxing, and targeted attacks. McLaughlin added that rhetoric from leaders like Newsom has fueled an increase in assaults on federal officers.

Newsom countered that claims of rising attacks are unsubstantiated. “There’s an assertion that somehow there is an exponential increase in assaults on officers, but they will not provide the data,” he said, accusing federal officials of spreading “misinformation and misdirection.”

Legal scholars have weighed in on the debate, with University of California, Berkeley constitutional law expert Erwin Chemerinsky noting that federal employees are generally subject to state laws unless compliance would interfere with their duties. “For example, while on the job, federal employees must stop at red lights,” he wrote in the Sacramento Bee.

The law comes shortly after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Trump administration’s sweeping immigration operations in Los Angeles. Democratic lawmakers in other states, including New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, have introduced similar proposals, citing the need to protect immigrant communities and prevent abuses by unidentified officers.

Alongside the mask ban, Newsom also signed the California Safe Haven Schools Act, which prohibits immigration agents from entering schools and health care facilities without a valid warrant or judicial order. The measure requires schools to notify parents and teachers when agents are on campus. Assembly member Al Muratsuchi, who sponsored the legislation, said the law ensures students are able to learn free from fear of deportation.

Earlier this year, California lawmakers also allocated $50 million to the state’s Department of Justice and legal groups to fund litigation against the Trump administration, resulting in more than 40 lawsuits. Together, the new measures reflect California’s increasingly confrontational sta